Bodily Autonomy Is About More Than Abortion Access

The concept also relates to discussions of disability, mental health, gender expression, and religion.

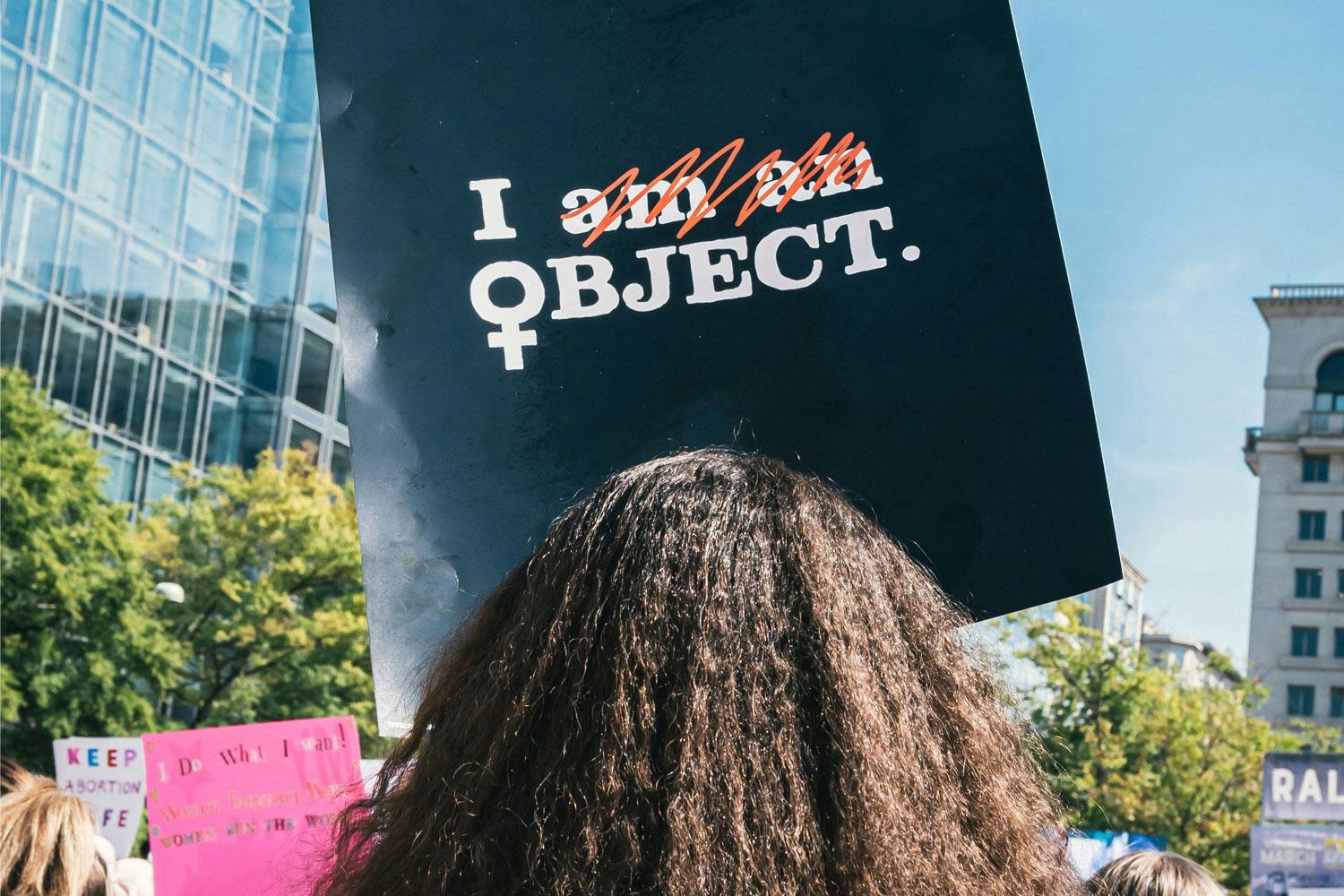

For many, the phrase “bodily autonomy” brings abortion access to mind, especially since the 2022 overturning of Roe v. Wade—the 1973 supreme court decision that legalized abortion throughout the US. This latest court decision means that American states can regulate abortion within their borders.

But the concept of bodily autonomy also applies to trans rights, disability justice, mental health, and even what a person can wear on their body. That’s a wide range of topics, so let’s unpack how these issues intersect.

What is bodily autonomy?

At its core, bodily autonomy refers to having individual control over what does and does not happen to our own bodies: how they’re dressed, how they’re fed, who touches them, and for what reasons.

Whose bodily autonomy is at risk?

When laws protecting bodily autonomy are struck down or overturned, the groups that end up in even more precarious circumstances are those who have rarely had control over what happens to their bodies—including people who are disabled, undocumented, gender-diverse, Black, Indigenous, and/or can get pregnant. The risks are real, and a lack of bodily autonomy can prove fatal.

A 2017 study published in the medical journal Contraception found that women reported substantial worry over contraception and abortion access after the 2016 election. The study found that its subjects considered “the potential for restricted access to affordable contraception and abortion,” after the election to be “an unacceptable limitation on bodily autonomy,” based on 449 online survey responses.

While that research only surveyed women, University of Maryland community health professor Dr. Shanéa Thomas notes that it is crucial to use inclusive language when discussing abortion. The fact that abortion access can also be a concern for people who don’t identify as women is why Thomas—who uses “he” and “she” pronouns interchangeably—developed a clinical tool for mental health professionals to use in discussions about abortion with LGBTQ+ clients.

The concept of bodily autonomy is relevant to a wide range of current conversations, including the Black Lives Matter movement, religious expression, and trans, queer, reproductive, and disability rights.

How does legislation impact bodily autonomy?

Abortion legislation varies across the US, so individuals who get an abortion in a state where it is deemed illegal can now be charged with murder. If the individual is not a naturalized citizen, they could also be deported by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Legislation can even impact what a person puts on their body. In Quebec, the provincial Act Respecting the Laicity of the State (commonly referred to as “Bill 21”) bans public service employees—like teachers and government lawyers—from wearing religious symbols such as hijabs, crosses, turbans, and yarmulkes.

How can bodily autonomy be promoted?

The university where Thomas works recommends using inclusive language to challenge the outdated assumption that there are only two genders. For instance, UMD advises against on-campus references to “he or she” in favour of noting all genders. Thomas notes that this tip can apply to many other settings, as all individuals would benefit from examining their biases and using more inclusive language.

She says it’s also helpful for people to have access to resources like pamphlets about reproductive rights, handouts that highlight ableist terms to promote disability justice, or an explainer about why the Black Lives Matter movement is needed. Individuals who are marginalized on multiple fronts rarely have as much power to promote bodily autonomy as organizations do, which is why institutions like universities have a responsibility to develop protocols to promote these ideas.

In September 2022, a different kind of initiative was launched by Queer Crescent—an LGBTQI+ Muslim advocacy group based in Oakland, CA. In response to the growing number of US states with anti-trans and anti-abortion legislation, the Muslim Fund for Bodily Autonomy was created to provide up to US$575 for individual Muslims to use on gender-affirming, reproductive, and mental health care.

Can research help promote bodily autonomy?

Dalia Mahgoub, Queer Crescent’s advocacy director, often experiences threats to their bodily autonomy as a biracial Muslim nonbinary femme. Mahgoub—whose pronouns are “they” and “them”—observes that people who are engaged with Islam and those whose gender expression isn’t exclusively masculine or feminine are particularly at risk of having their bodies policed.

Part of Queer Crescent’s approach to supporting reproductive justice has been about getting a better understanding of how legislation impacts the daily realities experienced by people who are both LGBTQI+ and Muslim when navigating abortion access, gender-affirming care, and mental health support. Mahgoub says their organization has received over 500 responses to their survey of LGBTQI+ Muslims in the US regarding the experiences of this minority within a minority.

Bodily autonomy is about the right to access, envision, and conjure up what your gender, your health care, and your living conditions are.

Given the social erasure that can occur when LGBTQI+ individuals are seen as a separate group from Muslims rather than an overlapping one, this research is meant to surface actionable steps towards a future of bodily autonomy for people who are both Muslim and LGBTQI+ in the US. The survey closed in October, so the data that was gathered is now in the hands of researchers, but has yet to be made public.

How else is bodily autonomy relevant to issues of equity?

Although bodily autonomy is often associated with health care, Thomas highlights that it is about much more than that. “It is not only my ability to be able to move through the world and make choices for myself about health care,” he says. “But also the way that I want to show up and how I dress, the food that I want to intake in my body.”

The “autonomy” part is about the ability to make choices for oneself that do not affect another human being outside of oneself. As an example, Thomas describes how discussions around body size and disability often become about who gets offended by the bodies of others. She explains that a person’s ability to make choices for themselves can become increasingly threatened when a person’s body size and/or disabilities make those with power uncomfortable.

How does marginalization impact bodily autonomy?

Research shows that people with marginalized genders and racialized bodies experience profound limits on their bodily autonomy. For instance, Mapping Police Violence estimates that Black Americans are 2.9 times more likely to be killed by law enforcement officers than white people. For Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the US, that number is even higher: a shocking 3.8 times. And the Council on American-Islamic Relations’ 2022 Civil Rights Report shared that the organization received 6,720 civil rights complaints from American Muslims in 2021, including discrimination and hate crimes that, of course, often limit bodily autonomy.

In addition to the professional experience that Thomas and Mahgoub possess, their lived experience as trans Black and brown professionals informs their insights as well. For Mahgoub, bodily autonomy is about “the safety and right to access, envision, and conjure up what your gender, what your health care, what your living conditions [are]—what you want to do with your body, whether that’s how you choose to present, or in your religious identity.”

What can you do to support bodily autonomy?

Whether you have thought critically about whose bodies are deemed disposable before now or you are delving into these tensions for the first time, you can make a difference on this issue.

For Thomas, it starts at home with his child. He remembers being a kid who was uncomfortable with having to kiss and hug people out of a sense of obligation. So Thomas asks his own child (and the little one’s stuffed animals) for consent before giving them kisses goodnight. Thomas explains that this act lets his child know it is ok to decline physical affection.

Mahgoub believes it is the responsibility of every member of society to work towards equitable outcomes for all bodies. That may look like protesting discriminatory legislation or donating to causes that promote and uphold bodily autonomy for individuals regardless of gender, age, ability, or skin colour.

“Everyone needs to care about bodily autonomy,” they say. “It’s incredibly important and it’s our divine right. And that’s why it is our tagline: Bodily autonomy is sacred. Self-determination is holy.”