In This Game, Bangalore’s Lakes are at Stake

An interactive theatre game aims to inspire people to save lakes in India’s tech capital.

Sarakki Lake in Bangalore, India

Long before Bangalore was known as India’s tech capital, it was known for its 200 lakes. But the title City of Lakes no longer holds true. In the face of rapid urbanisation and pollution, many have disappeared or turned into dead zones. Concerned that many Bangaloreans don’t understand the lakes’ plight, a local playwright has created Once There Was a Lake, a game that aims to spur conversations about ecology.

“I thought about what art can do,” explained creator Chanakya Vyas, artistic director of the theatre company Indian Ensemble. “…It can make people more aware, more conscious. It can make people see something that they don’t see, while keeping it playful and entertaining.”

A city of lakes

Bangalore lacks a major water source like a large river, so Kempe Gowda, a chieftain who founded Bangalore in the 16th century, built more than 100 lakes. Over the years, rulers and communities added to this system, which is made up of a series of interconnected reservoirs (known locally as “tanks”) that gather water from streams and rainfall.

“Bangalore never had lakes. They were tanks made by building bunds,” explained Naresh Narsimhan, a local architect and urban designer. The lakes often led to the establishment of new villages (now annexed by Bangalore). They helped with flood control, recharged groundwater, and created opportunities for fishing, while providing water for drinking, irrigation, and livestock.

Some lakes have grabbed international headlines by foaming and catching fire.

Only a handful of lakes remain healthy. Urban growth has sounded the death knell for many others, thanks to new buildings, the accumulation of silt, uncontrolled weed growth, and garbage dumping. Some lakes have grabbed international headlines by foaming and catching fire, due to a buildup of inflammable gases like methane from untreated sewage, industrial effluents, and solid waste.

But the story of Bangalore’s lakes is also a story of citizen activism. With the resolve to save these water bodies, citizen groups and campaigns have emerged in the last decade. Retirees, schoolchildren, techies, filmmakers, professional environmentalists, and homemakers are all actively engaged with conservation efforts. Volunteer groups draw attention to the problem, file petitions, work with authorities to revive the water bodies, and meet on weekends to pick up garbage in and around lakes.

A game for ecology

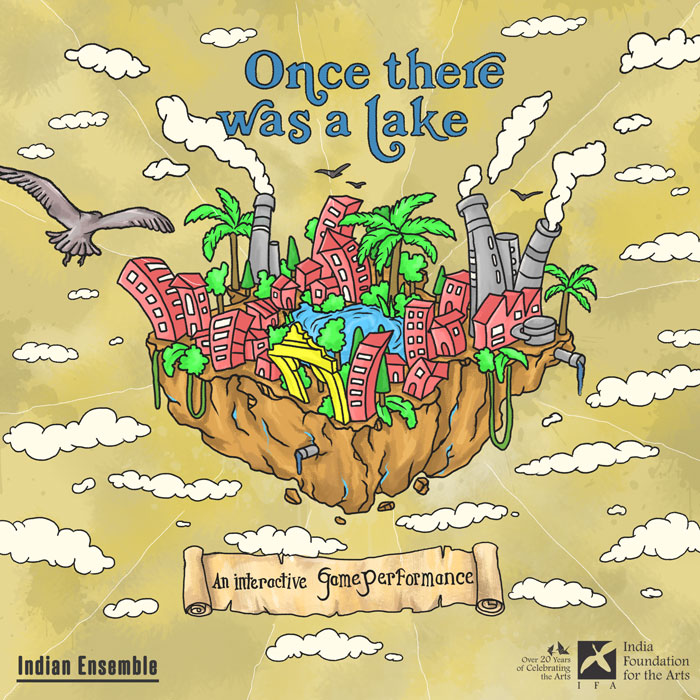

Once There Was a Lake aims to draw more citizens to the effort. A confluence of folk performance, traditional board games, live action role-playing, and theatre, the game—which was created with a grant from India Foundation for the Arts—is designed to be intimate, with room for up to 12 players.

It begins with a folk song about Dugilamma and Gangamma, water goddesses worshipped by the local Kannada community. Then, an actor narrates the story of the players’ neighbourhood, which has been cursed by the goddesses and run out of water.

“As villages turned into towns, towns into cities and cities into smart cities, one by one [the lakes] disappeared. What lies in the middle of your neighbourhood is a vast dry patch of land,” the actor says. “Gangamma and Dugilamma are still there — old, angry, and cranky — waiting for you to revive the lake and reimagine your neighbourhood.”

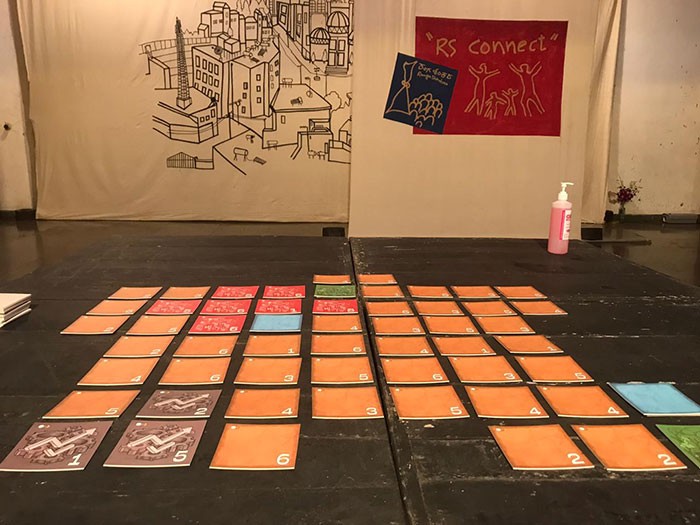

Chanakya Vyas demonstrating Once There Was a Lake to a Bangalore audience

A grid stands in for the neighbourhood, with cards representing dry land, water, greenery, industry, and settlements. Resources shift throughout the game as players make moves, like laying greenery on dry land or industry on water. They are motivated by victory conditions outlined on their cards. One might need to build industry, while another is focused on greenery. By throwing light on this tug of war between urbanisation and ecology, the game sensitizes participants to issues like replacing lakes with buildings and cutting down trees to make way for a highway.

Actors read out stories at regular intervals to highlight environmental challenges. The story of a crow and a vulture underlines citizens’ indifference to their surroundings. Flying over a neighbourhood, the birds are disturbed to find a lake being filled with mud. They try to alert a human who is too busy watching a melting glacier on her smartphone to take in her surroundings.

A close-up of the game’s playing card grid

Engaging citizens in revival

Vyas moved to Bangalore in 2012 and settled in Sarjapur, an IT cluster in southeast Bangalore where Kaikondrahalli Lake had been restored two years earlier. Urban development and garbage dumping had blocked water flowing into the lake, turning it into a polluted bed of water and trash. In 2008, a group of residents, architects, environmentalists, and ornithologists urged the local municipal body (known as BBMP) to revive the lake. The citizens’ group transformed into a trust that has signed a memorandum of understanding with BBMP to help maintain the lake.

“It was inspiring to know that it was a marshy, empty land and, by the time I came, it had been turned into a lake park,” said Vyas. “We assume these things are done by the government because it is their duty. But here, the authorities were pushed by the citizens.”

We assume these things are done by the government because it is their duty. But here, the authorities were pushed by the citizens.

The story stuck with Vyas, who later realised many locals thought reviving lakes was too complex for them to get involved. Once There Was a Lake is his response.

“Every choice they make on the board has a consequence. For instance, if we build too many industries next to the waterbody, definitely the waterbody will get polluted,” said Vyas. “It makes players aware of ecological issues.”

Had it not been for the pandemic, Vyas would have mounted full-fledged performances by now. He is contemplating an online version of the game and the team is conducting trial sessions when it can. Surbhi Rao, a corporate lawyer and theatre enthusiast, attended an abridged game at a Bangalore theatre space, which prompted him to think about the lakes in his neighbourhood. “More than anything else, it encourages a conversation,” Rao said.

Rethinking lakes

Harini Nagendra is a professor of sustainability at Azim Premji University and a local ecologist. She wrote a book on human-nature interactions in Bangalore from 6th century CE to the present. “The role of communities in reviving, restoring, and maintaining lakes in Bengaluru is absolutely critical,” she said in an email. “Innovative and immersive activities like what Chanakya has designed are essential — they draw people in and engage them in a way that talks and discussions cannot.”

V. Ramprasad, the founder of Friends of Lakes, an environmental group that has breathed life back into many of Bangalore’s lakes, hopes efforts like Once There Was a Lake shift the public narrative on lake conservation. He worries the public is more concerned about using lakes for leisure than conservation.

Innovative and immersive activities draw people in and engage them in a way that talks and discussions cannot.

Ramprasad points to Sankey Tank, a reservoir built in 1882 by the British. Today, it is part of a popular park. Responding to complaints about congested walking paths, BBMP is considering adding another path. This has upset activists like Ramprasad who worry that would shrink the lake.

It is in this context that Once There Was a Lake aims to lead citizens on a path of inquiry about their surroundings. Like the players in the game, a city that was once replete with man-made lakes wrestles with decisions that could preserve and revive them or destroy them for good.

Print Issue: Winter 2021

Print Title: Lakes at Stake