Turning Up the Volume on Greener Guitars

Guitars are traditionally made from “tonewoods.” Their growing scarcity has experts looking at other options.

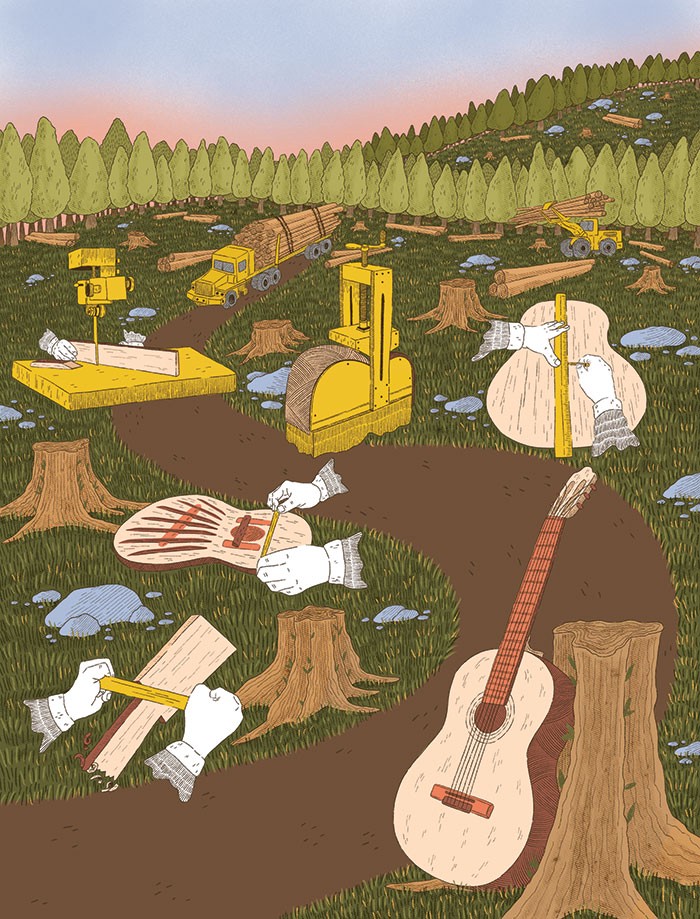

To the untrained eye, a pile of logs or slab of wood might appear uninspiring, lifeless. To a luthier, they can hold the key to music yet unplayed. An instrument-builder can look at this raw material and see the finished product: carefully joined wood, polished surfaces, and stretched strings ready to come to life in a guitarist’s hands.

Guitars can be a tangible journey, connecting disparate parts of the globe all in one instrument: a fretboard of dark ebony from Cameroon, a soundboard of golden Sitka spruce from Alaska, a body of ruddy sapele from Ghana. Musicians treasure their instruments for cultural, spiritual, and artistic reasons, but may not know the ecological stories built into their prized possession.

For centuries, luthiers have selected “tonewoods” like spruce and rosewood for their acoustic properties. But some tonewood species have become vulnerable, making them harder to source for those who wish to work with them, and causing others to question whether it’s ethical to do so. Faced with these challenges, environmentalists, researchers, and luthiers alike are seeking ways to make instruments whose materials and ecological bonafides both ring true.

Worrying overtones

Every continent with forests produces tonewoods, which include: mahogany, maple, Sitka and red spruce, ebony, Brazilian and Indian rosewoods, and koa. An article on guitar manufacturer Fender’s website describes woods on this list as having tones that are “punchy,” “transparent,” “powerful,” “rich,” and “sparkly.”

While instrument-making uses only a tiny proportion of harvested wood, luthiers are increasingly concerned about the sustainability and ethics of using certain tonewoods. Sitka spruce, for example, is one of the most popular woods in guitar-making, valued for its sound and durability. But the ideal Sitka for guitars is at least 400 years old, and logging old-growth forests is controversial, even if the species being logged isn’t endangered.

Let’s pause briefly to discuss endangered species. This article refers to two resources that assess whether a species is threatened. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is an international treaty whose “aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of the species.” There are three CITES appendices, each for species under different levels of threat: Appendix I, “threatened with extinction”; Appendix II, “not necessarily threatened with extinction” but still in need of protection; and Appendix III “protected in at least one country.” The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species marks species as being of the “least concern,” “near threatened,” “vulnerable,” “endangered,” “extinct in the wild,” and “extinct,” if it has data about them.

It is a tragedy to see wood from 400-year-old trees made into budget guitars that aren’t playable and won’t last.

So, back to Sitka spruce. It isn’t listed in CITES and is rated of “least concern” on the Red List, but there are plenty of arguments made against logging 400-year-old trees. “Guitar industry figures are coming to grips with the ethics of using old-growth Sitka, and it may be that the line is looming where it is no longer justifiable,” Dr. Chris Gibson wrote in an email. Along with Dr. Andrew Warren, a colleague at Australia’s University of Wollongong, Gibson wrote The Guitar: Tracing the Grain Back to the Tree, published earlier this year. To research the book, Gibson and Warren conducted interviews and visited forests on five continents over six years.

“Burdening guitar makers with the entire ethical burden for Sitka’s future is unfair,” continued Gibson, who has no relation to the guitar-making Gibson family. He pointed out many factors can be considered when deciding whether using a particular species is ethical: threats to the species, but also First Nations’ rights, biodiversity loss, and the purpose it’s being used for.

“It is a tragedy to see wood from 400-year-old trees being made into budget guitars that aren’t playable and won’t last, simply because large scale offshore manufacturers use their market power to leverage down prices with timber suppliers,” Gibson said. “But at the same time, the guitar industry is a tiny player compared with industrial forestry, monocultural plantations, and most other timber-dependent industries.”

Another controversial tonewood is ebony, prized by luthiers as a material for fingerboards. There are over 700 species of Diospyros around the world, and only a few have solid black heartwood. It has been threatened due to illegal logging, agriculture and other factors. Madagascar banned exports of both ebony and rosewood (genus Dalbergia) in 2010.

In 2013, all Diospyros and Dalbergia from Madagascar were listed in Appendix II of CITES, helping to shelter them. In 2019, the CITES standing committee recommended continuing a trade suspension on Malagasy rosewoods and ebonies it first instituted in 2013. The committee also asked Madagascar to take more action against illegal logging.

“Shortages of rosewood and CITES controversies in the guitar industry are the tail end of an ongoing, uninterrupted process of colonization, urbanization and development,” Gibson and Warren wrote in The Guitar. They also pointed to the Chinese market for rosewood furniture as a factor in its disappearance, noting that “an expertly crafted rosewood bedroom suite can reportedly sell for as much as US$1 million.”

Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra) is treasured for guitar-making, but the IUCN Red List marks the species as “vulnerable” due to logging and deforestation. (“Vulnerable” species “have a high risk of extinction in the wild.”) The species is also listed in Appendix I of CITES.

Beyond conservation issues, harvesting trees valued as tonewoods can sometimes cause human rights concerns.

The largest guitar manufacturers have largely switched from Brazilian rosewood to Indian rosewood due to declining supply and quality, according to Gibson and Warren. But Indian rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia), is also listed as “vulnerable” by the IUCN.

“The possibility that Brazilian rosewood could one day return as a factory guitar species seems forever gone,” wrote Gibson and Warren. “Grieving for losses and past mistakes will be necessary.”

Beyond conservation issues, harvesting trees valued as tonewoods can sometimes cause human rights concerns, according to Rolf Skar, a special projects manager with Greenpeace USA.

Skar compared certain woods to “blood diamonds” when looking at how they might be used, saying that because of their value, unethical harvesting can lead to deforestation, damage to land belonging to Indigenous peoples, and supporting dictatorships. The amount harvested doesn’t always fully represent the problem, he said, since the “first cut can be pretty deep.”

“It’s the thing that starts the domino effect of full deforestation and human rights abuses and land-grabbing in these places because of the high value.”

Concerted efforts

Given the downsides of using traditional tonewoods, environmentalist groups, guitar manufacturers, and academics are all involved in promoting ethical harvesting or exploring alternatives. An early effort in this direction was Greenpeace’s Music Wood campaign. In 2007, the nonprofit partnered with major guitar manufacturers like Fender, Martin, Gibson, and Taylor to encourage the Sealaska logging corporation to seek Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification for forests where Sitka spruce are harvested.

The manufacturers were interested in protecting future wood supplies. Skar gave the example of Martin Guitars (founded in 1833). “They started experiencing something they hadn’t seen before: ‘We can’t get that wood like we used to. What’s going on?’”

While the campaign didn’t achieve its goal, Skar says the partnership created opportunities for conversations with forestry interests that wouldn’t have happened without the guitar companies. It helped Greenpeace understand the companies’ tonewood needs, and created a foundation for future collaborations among instrument companies.

If you can make it valuable to grow maple, you start making an argument for re-invigorating the diversity of the local forest.

Some more recent efforts have focused on planting new trees. Pacific Rim Tonewoods (PRT) — a sawmill in Concrete, WA — is working with Taylor Guitars to plant koa in Hawaii. “We’re making that forest from what is now a grassland, from what was 150 to 200 years ago the biggest koa forest in Hawaii,” said PRT founder Steve McMinn “It’s not reforestation at this point because there’s no remnant of the original forest in the soil.” Koa isn’t listed in CITES, and is deemed of “least concern” by the IUCN, but McMinn and Taylor want to ensure a long-term source for the wood.

PRT also started the 100 Figured Maples Project to create genetic lines of fast-growing big-leaf maple trees that have favored figuring—ripples and waves in the wood grain—for use as the back and side pieces of guitars. The project is early in its development, and admittedly not critical to the industry as other woods are available. But McMinn said it could help both luthiers and local forests.

He explains that this native maple species has often been eliminated from working forests in the Pacific Northwest in favor of lumber species like Douglas fir. And while they’re not currently classed as endangered, recent studies show they’re threatened by climate change. “If you can make a reason for re-introducing it and you can make it valuable to grow maple,” McMinn explained, “you start making a good argument for re-enriching, for re-invigorating, the diversity of the local forest.”

Another effort, Taylor Guitars’ Ebony Project, is working to grow and sustainably harvest ebony, while also changing minds about using marbled ebony, which contains natural streaking and variations in color. According to the company’s website, co-founder Bob Taylor realized a large amount of ebony was wasted if it wasn’t the pure black traditionally used for instruments. He committed to using marbled ebony in order to reduce waste. The company also now co-owns an ebony mill in Cameroon and works to replant ebony there. Taylor switched to sourcing from Cameroon after realizing illegal logging and sustainability issues plagued ebony from Madagascar even before exports were halted.

Initiatives to restore forests valuable to instrument makers extend beyond tonewoods and the guitar industry. Bowmaker Marco Raposo and British non-profit RAIN (which stands for “regenerative agroforestry impact network”) launched the Trees of Music campaign in 2021 with a focus on saving Pernambuco trees (Paubrasilia echinata), which are favored for making bows for stringed instruments. Pernambuco is listed in Appendix II of CITES, and as ‘endangered’ by the IUCN.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, 96% of coastal Pernambuco forests are now gone. Trees of Music announced plans to plant 50,000 Pernambuco trees within two years, with half of the trees intended for creating bows and half to help restore the forest.

Greenpeace’s Skar said tonewoods can be sustainably harvested, but there must be restraint. Using old-growth Sitka spruce as an example, he suggested it could still be carefully used if properly valued and thoughtfully cut. “You can make soundboards for cellos and everything else for a long time to come,” he said. “As long as you live within the limits … and you’re more selective.”

McMinn also believes tonewoods can be ethically harvested. He added that other industries use far more lumber. “Meanwhile, houses have burgeoned from 800 feet to 1200 square feet to 2500 square feet, and those are huge drivers of lumber,” he said.

Toning it down

A 2018 study published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America found that the type of wood used for the back and sides of a guitar may not make a large difference in sound quality. Part of the study tested six instruments built with with backs and sides made from different woods, some rare and highly valued (Brazilian rosewood, Indian rosewood, and Honduran mahogany), others “less well regarded” and more widely available (North American maple, claro walnut, and sapele — which is rated “vulnerable” by the IUCN but not listed by CITES). All had Sitka spruce soundboards, the top piece of the instrument McMinn calls “the engine of the guitar.”

For the study, 52 guitarists were given the different instruments to play. To prevent them from visually identifying the woods, they wore goggles and played in a dark room. Afterwards, the guitarists assigned “very similar” ratings for each instrument’s sound quality.

In a press release, one of the study’s authors — Lancaster University’s Dr. Christopher Plack — summarized its findings: “Overall our results suggest that the back wood has a negligible effect on the sound quality and playability of an acoustic guitar, and that cheaper and sustainable woods can be used as substitutes of expensive and endangered woods without loss of sound quality.”

To aluminum and beyond

Some luthiers are avoiding wood altogether and exploring materials ranging from aluminum to linen to carbon fiber.

Aluminati Guitar Company in Asheville, NC, makes guitars from aluminum and lucite. James Little, Aluminati’s CEO, began the company in 2009 to spread the love of aluminum guitars he first developed on a friend’s 1970s Travis Bean model. “It was a little hard to play,” he said, “but something about the sound — it hooked me in.”

Unlike the prohibitively heavy aluminum guitars of the past, Aluminati’s models benefit from new technology that allows Little to build instruments that are at least as light as their wooden counterparts.

While Little appreciates their sound, he also values their longevity. Aluminati instruments are largely made from recycled materials, and don’t need to be tuned or maintained as frequently as wooden guitars, he said. They can also be recycled rather than trashed. (Repairs to broken, cracked, or warped wooden instruments can become expensive.) Waste material from Aluminati production is sent back to the Alcoa Corporation for recycling as well.

They’re expensive, though, ranging from US$2,899 to US$5,700. Decent entry-level wooden guitars can start as low as US$149, though prices do increase significantly from there. Gibson’s electric guitars range from US$1,000 to US$3,999, with custom instruments listed up to US$9,999.

San Francisco-based Blackbird Guitars has created Ekoa, a composite material made from linen fiber and resin derived from industrial waste, which it touts as an environmentally friendly and durable alternative to wood. “It is lighter than carbon fiber, stiffer than fiberglass and makes a better soundboard than spruce because of its superior stiffness-to-weight values,” the company states on its website. Guitars made from it retail for approximately US$3,000 to US$4,000.

The traditionalists will likely insist on “classic” woods…but the market is opening up for alternative materials.

Another company, KLOS, uses carbon fiber in its designs. Typically derived from fossil fuels and difficult to recycle, carbon fiber isn’t an obvious environmental choice (though in future it may be made from algae). The current argument in its favor is its incredible durability, reducing the need for musicians to replace their instruments.

Carbon fiber guitars stay in tune longer, have more consistent tone, and are less prone to damage, according to KLOS. On its website, the company shows a carbon fiber ukulele surviving being run over by a Prius. (It is afterwards crushed by a heavier Toyota 4Runner.) They’re also cheaper than the previous examples, with a travel-sized instrument priced as low as US$839.

KLOS makes a controversial claim: “Wood guitars had their place for a couple hundred years, but the times have changed.”

Wood is still the traditional favorite among guitar-buyers, but Guitar-author Gibson said consumers are becoming receptive to alternatives if they’re well-made.

“The traditionalists will likely insist on ‘classic’ woods, and frankly, most players believe that you need wood rather than synthetic materials,” said Gibson. “But the market is opening up for alternative materials. Some of that demand for alternatives will be driven by environmental concern. But a lot of it will be driven by other factors such as playability, maintenance, and sound.” Alternative instruments must be made affordable to gain popularity and be accessible to children and those with limited budgets, he added.

With consumers interested in sustainably made instruments, and non-traditional materials rising in popularity, Aluminati’s Little sees other companies looking at their options. “More and more companies are starting to get on board with building sustainable instruments and using different materials other than wood,” Little said.

Solo efforts

Buying new instruments made from alternative woods or materials isn’t the only way individual musicians can help effect change. Shopping for quality used instruments, or repairing old ones are also good ideas.

“Encourage the small industry that does repairs and refurbishing of instruments,” Greenpeace’s Skar suggested. “That can go a long way.” Consumers buying new instruments can look for those made with FSC-certified wood, he added.

Sawmill-owner McMinn suggested consumers can purchase guitars made by manufacturers interested in ethical and sustainable practices.

Ultimately, author Gibson feels the question of sustainability in guitars will be answered in a variety of ways: “Use of more plentiful plantation timbers, use of local, native and urban trees, careful salvaging, and composite and manufactured materials such as laminates, carbon fiber and metals are all part of the mix,” he said. “Like many other industries, the guitar industry is gradually becoming a kaleidoscope of niches rather than an oligopoly dominated by a small number of companies and standard designs.

Consumers should encourage the industry that repairs and refurbishes instruments. That can go a long way.

Customers can also let companies know they want ethically harvested materials used in their instruments. Skar recommended musicians reach out to manufacturers through their customer service lines to ask about environmentally friendly options with questions like “Where is this wood coming from? … What can you tell me about the sourcing of this wood, and how do I know it’s free of human rights abuses?”

Even though customers might feel too small to cause change, Skar said the pressure can add up.

The more manufacturers are asked about the source of their wood, said Skar, “the more they’ll realize their customers care.”

Print Issue: Fall/Winter 2021

Print Title: Music to Green Ears