Science Still Isn’t by Everyone, for Everyone

The lack of diversity in science and tech isn’t new, but fresh thinking might finally make these fields more inclusive.

Decades of work to increase the proportion of women working in science and technology mean that by 2016, 34% of Canadians with scientific degrees identified as women. But recent statistics show less than a quarter of those working in scientific fields identify as female. Dr. Samantha Yammine has made it her life’s work to make the second number match the first.

“Science should be by everyone, and for everyone. And that hasn’t always been, and still isn’t the case,” says Yammine, whose work includes participating in events that promote inclusion in the fields often known by the acronym STEM (which stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math). In this article you will also encounter STEAM, in which the A stands for “arts and design.”

“Anyone who is marginalized by their gender — whether they’re young girls, women, non-binary, trans — we need them in STEAM,” says Yammine. “We need to have proper representation, to have people with a diverse range of experiences.”

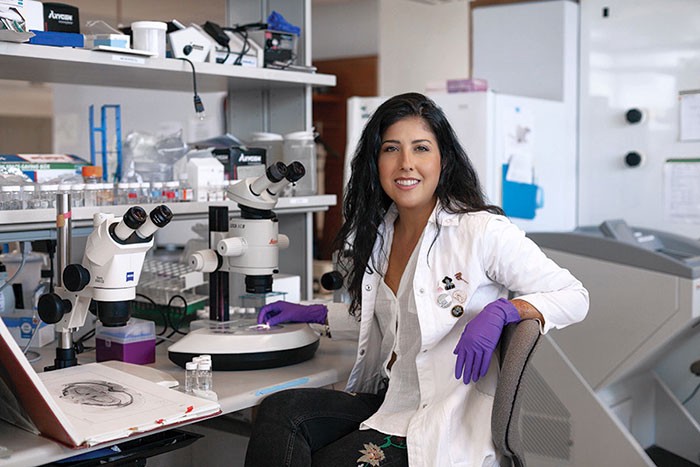

Yammine is a science communicator with a PhD in neuroscience from the University of Toronto, who uses the moniker Science Sam. She works to increase representation in the sciences of all youth marginalized because of gender, and her advocacy puts a finer point on inclusion: welcoming youth to bring all the multi-faceted parts of their identities to their studies and work.

Dr. Samantha Yammine — aka Science Sam — wants kids who are marginalized in any way because of their gender to know that science needs them.

One way she does this is by speaking at events for youth. She was the keynote speaker for the annual Girls and STEAM event at Science World in Vancouver, BC, in November 2021. At the event, youth 11–13 years old who are marginalized because of their gender were invited to connect with mentors and explore careers in these fields.

Tracy Redies is the president and CEO of Science World, and she knows the issue of underrepresentation has not gone away. “The gender gap in STEM fields continues to be an issue with only a quarter of jobs today held by women,” says Redies. Among Canadian STEM graduates, men were almost twice as likely (42%) to work in STEM jobs than women (23%) in 2016. “Diversity in these fields is essential to ensuring that all voices and ideas are brought to the table and equally respected. It’s imperative that we start this process today.”

While recruitment to post-secondary programs may have increased, educational systems and workplaces in these fields do not support retainment. A World Economic Forum report tells us why: “Not enough teachers and career counselors have the training to help correct the gender imbalance in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.” This, combined with ongoing perpetuation of gender norms, continues to hold girls back.

The seeds of gender inequality start early, beginning with gender norms that become ingrained during early childhood education — for example, the conditioning that all boys like loud constructive play (with blocks, for example) and girls prefer social play. This continues through all levels of education, and persists in workplaces. UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) explicitly describes the inequalities experienced by women who do continue in their scientific fields as “a lower publication rate, less visibility, less recognition and, critically, less funding.”

The representation of women in STEM decreases as students progress along their academic and career paths.

Even now that women make up 44% of those enrolling in a first-year STEM program in Canada, they are still much less likely to work in STEM after they graduate. The representation of women in STEM decreases as these students progress along their academic and career paths.

Yammine explains that the “leaky pipeline” metaphor — often used in mainstream feminist circles to describe how women “leak” out of scientific fields — is faulty, and problematic. Yammine says this is a dangerous falsehood, and that the pipeline is working exactly as it was designed: to be exclusive. “And that’s what I want to fight against. I really want to empower youth to not feel that they have to change, to fit into the system,” says Yammine.

“This system needs to change — because it needs them more than they need the system,” she adds, emphasizing the need for more young Indigenous women in the full range of sciences.

According to Engineers Canada, a national regulatory body, just 14% of licensed engineers in the country are women, even after targeted recruitment campaigns. For instance, the “30 by 30” campaign began in 2015 with the goal of having 30% of engineers in the country be women by 2030. Studies have shown that 30% is seen as the “tipping point” that can shift organizational culture.

3% of Canada’s labour force are Indigenous, but only 0.7% of the country’s engineers identify as Indigenous.

Indigenous representation in STEM careers is only 2%, according to a webinar by the Conference Board of Canada. Engineers Canada data shows 3% of Canada’s labour force are Indigenous, but only 0.7% of the country’s engineers identify as Indigenous. Drilling down into that number, only 15% of that 0.7% are female. And only a third of the Indigenous people studying STEM are women.

“We need Indigenous engineers so badly,” says Yammine. “There are so many issues we see across the country where Indigenous expertise should be at the forefront and respected as its own branch of knowing things, and experience.”

Yammine wants to show the next generation of scientists the benefits of bringing their diversity into everything they do. “I want them to bring their whole selves. Giving their experiences and perspectives because that will make science better.”

When Yammine shares her voice, it’s with an awareness that she holds privileges based on how she’s perceived, “as racially white. I’m ethnically Arab, and I’m disabled, but you can’t tell by looking at me — and I have other types of identities.” This translates to responsibility, she explains. “Anyone who’s given privilege, to have a seat at whatever table, in whatever room — it is our job to make sure that we’re not just taking up space, we’re making more space for other people.”

Yammine says that, historically, people have tried to separate the social aspects of the world from science, and that simply doesn’t work. “We’ve tried to pretend that big parts of our world don’t impact the way you do research.”

Historically, many clinical trials largely consisted of cisgender, able-bodied young men. In the US, it wasn’t until 1993 that the Food and Drug Administration and National Institutes of Health mandated the inclusion of women in these studies. Until then, they were excluded if they were of “child-bearing age.”

The job of anyone who’s given privilege is to make sure we’re not just taking up space, we’re making more space for other people.

Yammine explains why this is problematic: “That led to many medicines not being properly tested or dosed for anyone who doesn’t fit into that category.” A decision was made about how scientific studies were done, “with negative impacts on real people, because we weren’t considering that there’s diversity in our population that should be represented at trial.”

How does this exclusion continue for other marginalized groups? While there have been improvements to ensure clinical trials are balanced between women and men, “there isn’t always representation across ancestries, people on different medications, different disabilities, or people who may be trans, medically transitioning,” says Yammine. The hope is that diverse research teams would be better at designing more inclusive studies.

This is where inclusivity training programs for engineering students and professionals — such as those offered by EngiQueers, a national collective of engineering student organizations — come in. These trainings raise awareness about topics such as systems of oppression and intersectionality.

Despite diversity, inclusion, and equity banners flying at many organizations, unconscious bias remains, and impacts retention. Engagement and recruitment events may have intentions of increasing diversity, but lack systems to support diverse participants. Science World doesn’t have numbers of how many Girls and STEAM participants have been Black, Indigenous, people of colour, or gender diverse. Madelyn Osborne, co-producer of Girls and STEAM, says tracking through self-identification during the registration process recently began, in the program’s fourth year.

Despite the amount of deep work that remains to be done, Yammine says she tries “not to be cynical.” She mentions that connecting with other activists gives her hope. Activists like the organizers behind Black AF in STEM, a collective that amplifies and supports Black STEM professionals working in natural resources and the environmental sciences, and organized last year’s Black Birders Week. Yammine notes, “We’re getting better and have more tools to build community. So people aren’t so siloed and isolated in this type of advocacy work.”

“I’m inspired by the grassroots movement,” Yammine says. “I think when it comes to bigger systemic change, people are starting to talk about things and use better language. There’s a lot of ‘talking the talk’ and now people like me try to hold the higher-ups to account — to actually do the things that need to be done.”

Yammine promotes inclusivity herself in a number of ways. As a keynote speaker and host at events like Girls in STEAM, she shows scientists marginalized because of gender can be leaders, addressing a problem identified by one journal article: “Lacking female role models make women avoid STEM majors or leave prematurely.” (The article argues that 50% of the scientists children are exposed to should identify as women.)

Lacking female role models make women avoid STEM majors or leave prematurely.

She also will only work on projects that commit to inclusion across a range of qualities that can be marginalized, including: gender identity and expression, body size, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, level of education, race, religion, ethnicity, and disability. She declines work that she sees as contributing to marginalization.

She also sets a high benchmark for accessibility. She asks venues and partners to ensure “all content created will be made inclusive to the widest possible audience.” This ranges from accessibility ramps and closed captions, to materials designed in palettes accessible for those with colour vision deficiency, gender-affirming washrooms and more.

For Yammine, outreach and mentorship programs “are not just about making young girls feel included. It’s for anyone marginalized by their gender in any way — whether they are intersex, trans, non-binary, questioning gender or fluid.” Yammine is committed to making sure “all those kids know I want to see them in science.”

“I want to make science an actual safe place where they can thrive and prosper and do the work that needs to be done.”

Correction: This article originally claimed that Dr. Yammine was involved in organizing Girls and STEAM at Science World. It has been updated to reflect the fact that she was a keynote speaker, but not an organizer.