The Decider: Print or E-Books

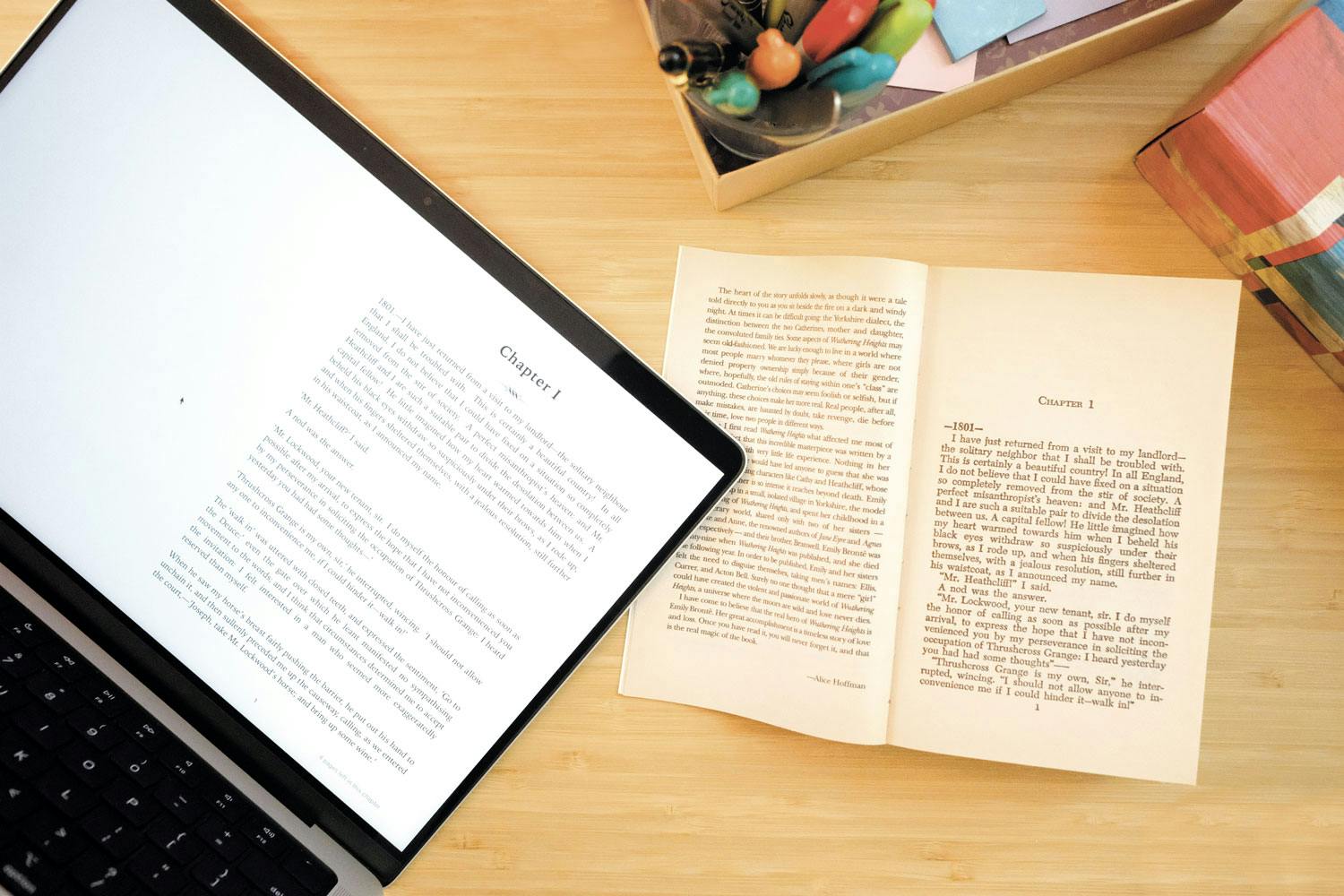

Most people have a preferred format for book reading. But is one better for the planet?

Many experts will tell you that reading e-books is the more sustainable option, but the truth is a lot more complicated.

As a reader, you have more options than ever when it comes to how you consume books. You could pick up an old-fashioned paperback for a familiar reading experience. Or you could use an electronic device and take your reading material with you digitally; you’d be joining about 90.5 million e-book users from the US, and 9 million from Canada, according to the Statista Global Consumer Survey.

But are e-readers actually better for the planet? Amazon and others with an agenda push this narrative, but the truth is a lot more complicated.

A US market research company, the NPD Group, reports that e-book sales were buoyed last year by a Covid-19 pandemic that made actual books harder to obtain. E-book sales grew 22% in 2020 and accounted for about one in six US book sales in mid-2020.

But with bookstores open again, e-book sales are now declining — by 8% in 2021, so they’re still higher than before the pandemic. Loyal print fans will tell you that the tactile experience of reading a book will remain a draw no matter how portable digital books can be — and even when sustainability is a factor.

It’s not easy to get a clear answer about the emissions caused by written materials, because every publisher measures its impact differently.

Actually, environmental concerns aren’t usually the main draw of e-readers, says Michael Rogowsi, office coordinator for the Canadian Federation of Library Associations. “If anything, the sustainability is a great by-product from the electronic format, even when you compare it with hosting costs and viewing costs,” he says. “But rarely is it the driving force, from my experience.” Instead, he believes, the convenience of the format is what makes e-readers so popular.

Carbon comparison

E-books have been around since Project Gutenberg digitized the US Declaration of Independence in 1971, according to the US Government Publishing Office. But it wasn’t until 2004 that Sony launched an e-reader for the public, followed by Amazon’s Kindle in 2007. Research about the environmental impacts of these devices began at about this time.

Unfortunately, it’s not easy to get a clear answer about the emissions caused by written materials, because every book, magazine, and newspaper publisher measures its environmental impact differently, and the statistics they use are not always directly comparable. Oft-cited studies on the topic also measure different factors in various ways.

In general, we know that books printed on virgin fiber (as most books are) require cutting down trees, which removes vital carbon sinks. And all book production involves chemicals for processing paper, glues, and ink, which each have separate carbon footprints. Paper book emissions are also caused by the transportation of physical copies, paper recycling, retail energy-use, and unsold books destroyed by publishers.

Locations where printing takes place matter, because different cities and countries have different manufacturing processes and power sources. So does whether a book is being printed on demand (resulting in potentially fewer unwanted copies), whether it has images in it (resulting in the use of more inks and more chemicals), and what kind of paper it uses (some papers are made whiter and more absorbent through bleaching).

One study found that replacing a paper book with a digital version would avoid emitting 50 kg of CO₂ equivalents.

What is clear is that the environmental impacts of a printed book have all happened by the time it reaches a reader. So second-hand purchases and library copies have a lower impact per reading than new books read only once.

The Green Press Initiative in 2008 did what it called the first study of the environmental impacts of the US book industry, finding that each book emitted 4 kg of CO₂ per book as a result of production, publication, and retail activities, with the industry as a whole emitting 12.4 metric tons a year.

In 2009, the Cleantech Group estimated that the average Kindle user would buy 144 e-books in four years, preventing the sale of 22.5 physical books each year, since Kindle readers bought 1.6 e-books for every paper book they would have purchased. The study estimated that, all told, e-book and e-reader sales would save about 9.9 million metric tons of carbon emissions from 2009–2012.

More recent studies have resulted in different numbers, based on varying assumptions and data. As part of his studies at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Joachim Felix Aigner determined in 2018 that replacing a paper book with a digital version would avoid emitting 50 kg of CO₂ equivalents. A 2018 Japanese case study in the Journal of Cleaner Production found that greenhouse gas emissions weigh in at 1.2 kg per paper book (1.1 if books are later recycled), while e-books had emissions of 0.3-.09 kg.

On the other hand, in 2020 researcher Pierre-Olivier Roy (then working at Québec-based life-cycle research center CIRAIG) attempted to determine whether student use of electronic textbooks reduced emissions over paper books. He found that — depending on how the paper books were produced — the threshold over which reading on an iPad emitted less than paper books occurred when a student was working with between 13 and 30 textbooks. Below the threshold, his calculations said paper textbooks would likely emit less than e-books.

Impacts of technology

Electronic devices have their own sustainability issues. These include mining for materials that go into electronic components such as the screen and central processing unit (the unit’s “brains”); battery usage; and the impact of data centers and services that store e-books. As pointed out by Roy in his CIRAIG research, electronic devices have a shorter shelf life (about three years) than paper books, and recycling electronics remains problematic.

Every electronic device also has a different carbon footprint, with e-ink devices like Kindle having less ecological impact than phones and tablets with liquid crystal display (LCD). Eri Amasawa, an assistant professor of chemical system engineering at the University of Tokyo, explained: “An e-ink display is mostly made of plastics and [requires] much less electricity to operate compared to an LCD display. An LCD… consumes 10 times more electricity than an e-ink display.”

Your reading’s impact depends on how often you pick up your e-reader and how often a paper book is shared.

But technology continues to adapt and evolve — and so do the companies making it. For example, if you visit the Rakuten Kobo website, you’ll find that the company purports to offset 100% of its emissions associated with the shipment of Kobo e-readers by planting trees.

Meanwhile, an Amazon representative claims that in the last two years, Kindle readers in the US saved 2.6 million metric tons of carbon by choosing e-books. Amazon doesn’t share its research, but claims to have conducted a life-cycle analysis that shows it has reduced its carbon footprint year-over-year. “We are incorporating recycled plastics, fabrics, and metals into many new devices,” said Rachel Praetorius, director of sustainability and hardware operations for the Amazon subsidiary responsible for Kindle.

The winner: It depends!

Although there is no way to generalize as a result of all the possible variables, many experts will tell you that reading e-books is the more sustainable option — but only if you read a lot.

For example, a 2017 study in the International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment by University of Tokyo researchers including Amasawa, calculated that paper books and e-books read on e-ink devices break even in terms of carbon emissions at 4.7 books. That is, once five new books are purchased, the annual emissions of reading paper books exceeds the annual emissions of e-ink reading (assuming that people are reading fewer than 11 hours per day).

In other words, your reading’s environmental impact depends on factors such as how often you pick up your e-reader and how often a paper book is shared. If you only pick up one or two books a year, or only ready copies shared among many people, reading paper books might actually be more beneficial for the environment.

Jean-François Ménard, an analyst at CIRAIG who recently created a life-cycle performance study on electronic books, concluded that the answer has to do with your behavior as a reader: where you buy, how you buy, and how you dispose of your reading material. “And the answer to those questions will maybe not identify which [type of] book is better, but they’ll give you pointers as how you can improve your footprint,” he said.

He also raises another complication: books don’t just provide content. People often have relationships with special books they love, and won’t discard them for that reason. “A book,” he notes, “is a very special product.”

Print Issue: Spring 2022

Print Title: Screen vs. Page